Once again, we handed over our little panther to a vet technician who carried him into the vet hospital. We were relegated to the parking lot for the next hour and a half. COVID regulations make what is already impossibly difficult worse. We understand the need to keep the medical staff safe and disease-free but separating us from Castiel at this time was so difficult. We wanted to be there to reassure him, to comfort him, to pat his little head. We wanted to see the doctors, see the facility, be reassured that he was in good hands. We wondered what was happening behind the curtain.

About an hour after handing him over to the technician, the surgeon called us. We put him on speaker phone so we could both hear. He wanted to know we were sure of what we were asking. He said, ” I can take it off but I can’t put it back on.” We weren’t sure… we weren’t sure of anything. We wanted to scream that. I’m sure we sounded a complete mess. We tried to breathe. We had a list of questions prepared ahead of time. We asked him about his experience with amputation. We asked about his experience with front leg amputation. Did he follow up with patients — how did they do? Did he think Castiel would adapt despite his age and tubbiness? He thought he would. He said it would be harder for Castiel with a front leg amputation because cats place most of their weight on the front. But he thought he would figure it out. He said he thought Castiel was otherwise healthy and that he would do okay during the surgery. He described the pain medicines that he would give and how we could manage Castiel’s pain. He said he would help us to make sure Castiel was not in pain. The surgery sounded incredibly scary – the removal of the whole leg and the scapula. Why aren’t there good prosthetic options. Why doesn’t Science know how to kill the cancer and save his limb? Why didn’t we study oncology. We felt useless.

We know we shouldn’t ask the question but we had to — you know the question. We all ask it. “What would you do if it was your cat?” What he said gave us pause. He said he would wait… he might assume more risk and gamble that he could wait a little longer until the cancer started growing and then maybe remove the leg. We didn’t know what to think. Was it like the stock market — some people are comfortable with more risk where others are more risk averse or did he maybe think Castiel wasn’t a good candidate and didn’t want to say so directly. We asked for clarification. He said it was like the stock market. He would gamble a bit more — take on more risk for perhaps quality of life, or at least that is how we understood it. But he also cautioned “that when the pathologist says the cancer will come back, in his experience, 99 percent of the time, it does.” He didn’t think removing the leg was the wrong thing to do. He left the decision with us. He explained that if the cancer spreads, it would shorten his life. He said the recommendation for this kind of cancer was usually to treat it with surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. He said he wasn’t an oncologist so he couldn’t speak to what was best for a particular cancer. We understood also that he was a surgeon, confident in his skills, possibly able to detect changes earlier and easier than us in his cat, and perhaps this went into his decision-making tree in answering our question.

We were uncertain. It is easier to make a decision when everyone agrees on what is best but that wasn’t what we were hearing. We had heard sometimes that vets try to get a feel for where the patient’s guardians want to go with treatment and then advise along those lines. We don’t know if this is true. We felt like we had received an independent opinion and we were grateful for it, even if it gave us pause. We were reminded of a friend who shared her experience with amputating the leg of her cat to try and beat cancer. In her case, however, the cancer had unknowingly already spread to the lungs and her cat only survived a year and a half. She said she was “haunted” by the experience. She said her cat didn’t adapt well and that “he was never the same.” We appreciated her honesty. Perhaps her cat didn’t do well because the cancer had already spread at the time of amputation or perhaps her cat was depressed by the loss of the limb. We can’t know, but we felt her pain and despair, and it was real and palatable — and it scared us.

A family member who had been a vet tech for several years said she wouldn’t do it. She said she had never seen a good outcome. She said she would let him live out his life as is and let him go. We were horrified.

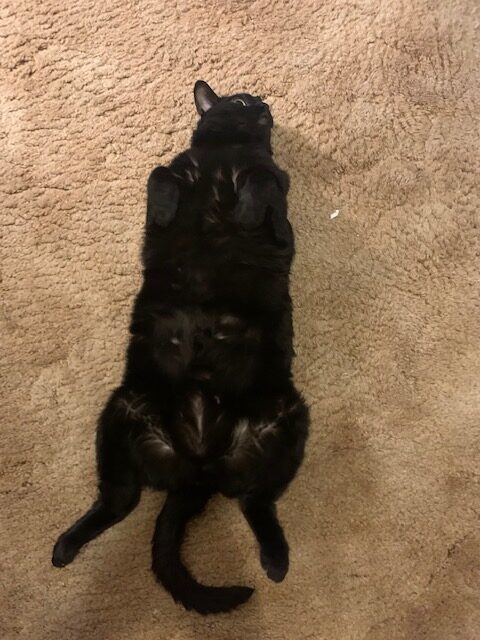

We went back and forth…we read more journal articles. We read books about how fibrosarcomas are treated in humans (much of it sounded similar). Should we rely on science and the information from the veterinary and oncology professionals or should we listen to family and friends who advocated for quality of life (no amputation) or letting him go. We couldn’t give up on him so it was between palliative care and surgery (and possibly adjuvant radiation). We changed our minds a million times a day. Emotionally, I can’t imagine him without his beautiful black paw that I have kissed countless times. I had nightmares imagining seeing it separated from him lying on a table. It was too much to bear. I wished I was the kind of person who could do something with stress — exercise more, throw myself at my work, drink like a fish, whatever — but I’m not. I just lie awake agonizing in the dark. I think we know that the science suggests that the best likelihood for prolonged life is to do the surgery and follow it with radiation. But science deals in likelihoods and medicine is not an exact science and never will be. There are too many variables — too many unknowns. This is the biggest decision we have ever had to make. What if we get it wrong? What if the naysayers are right? My husband tells me that we will know that we did our best. Is that enough? I don’t know. He’s our baby panther and we love him so much. He just can’t be sick.